From poetry to plastic: Al-Mutanabbi Street’s cultural identity withering

Shafaq News/ Once revered as Iraq’s literary sanctuary, Baghdad’s Al-Mutanabbi Street is quietly losing the essence that defined it for generations. Where shelves once groaned with poetry, philosophy, and political thought, plastic toys and school supplies now dominate the view.

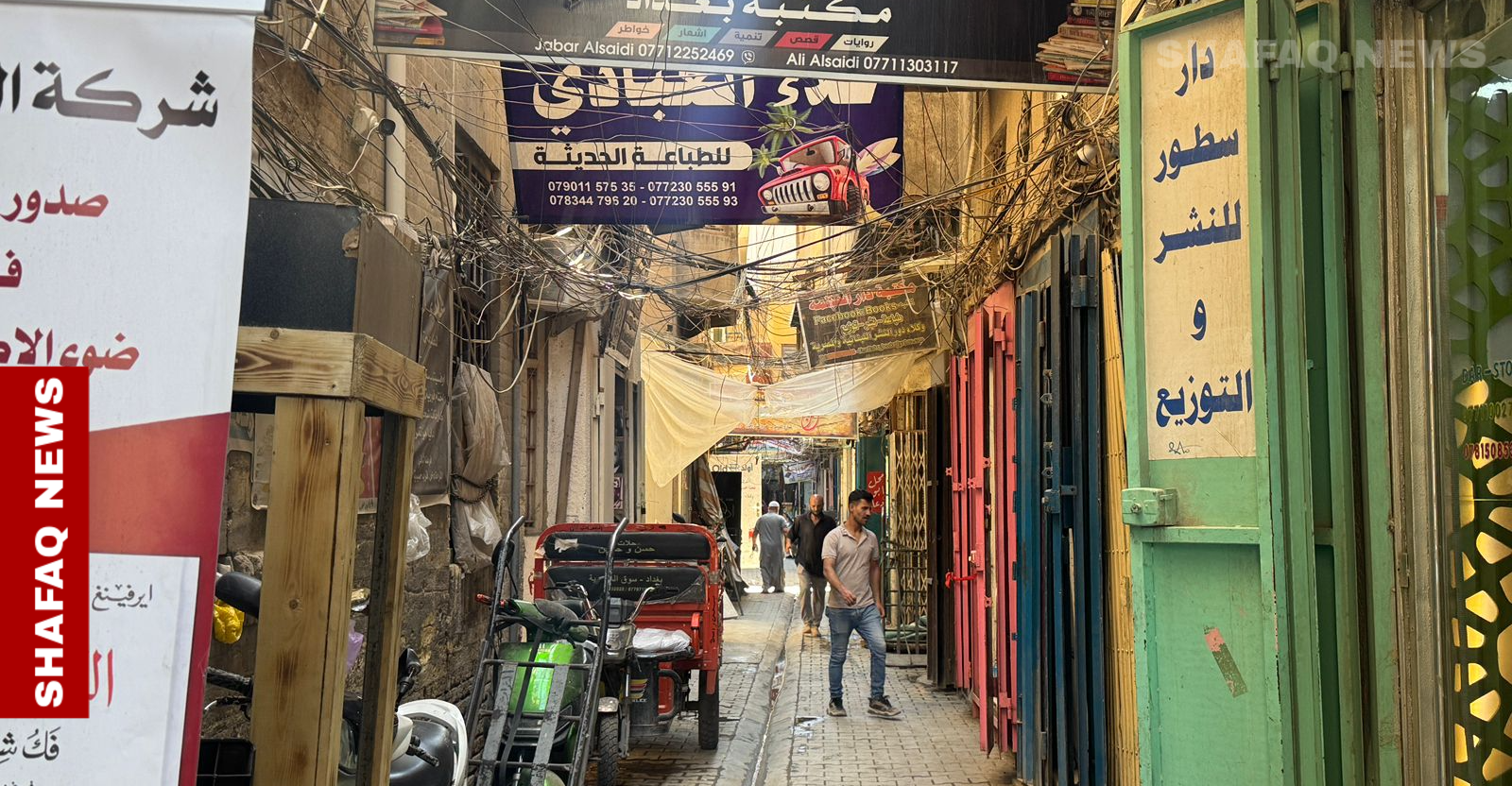

Booksellers are either closing or retreating into cramped alleyways, as the street’s cultural identity withers under the pressure of commercial priorities.

Approaching from al-Rusafi Square, visitors now encounter toy stalls and stationery booths long before glimpsing a single bookshelf. Once a proud avenue of scholarship, Al-Mutanabbi increasingly resembles a bazaar. Of the dozens of literary shops that once lined the street, only a handful remain visible.

The transformation is not just physical—it’s existential.

Books Retreat to the Shadows

Most surviving vendors have moved into narrow side alleys, or qasariyyas, hidden behind layers of commercial clutter. “They’re in there now,” an elderly visitor remarked, pointing toward a dim corridor barely wide enough for two.

Inside, these confined spaces house the remnants of a once-vibrant intellectual hub.

Publisher Sattar Mohsen Ali, who has worked on the street for decades, attributed the shift to both economic hardship and shrinking readership. “The street’s original identity was rooted in bookstores,” he told Shafaq News. “Pens and printers were always secondary. But today, stationery sells better.”

Rents along the main road range from 2 to 3 million Iraqi dinars per month (approximately $1,540 to $2,310)—far beyond what most literary businesses can afford. Many have relocated to modest alley shops where rent averages 350,000 dinars (about $270). It’s a tradeoff between public visibility and economic survival.

Page Turned: Books No Longer Pay

Books no longer sustain the shops that once thrived here. “We’re losing a book vendor every month,” Sattar lamented. “Digital media, social platforms, and financial stress have pulled people away from print.”

He warned that while online reading is popular, it often lacks scholarly rigor. “Academic work needs credible sources. Blog posts don’t count.”

Rampant piracy and unchecked photocopying have deepened the crisis. Unauthorized copies flood the market, leaving legitimate sellers struggling to compete.

Meanwhile, others have pivoted to school supplies, office tools, or closed shop entirely. The Saray redevelopment—initially seen as a revitalization effort—relocated several major literary outlets to a single building tucked away from the street’s foot traffic. Visitor numbers dropped. So did sales.

Institutional Neglect

Sattar criticized Iraq’s lack of public support for its publishing sector, stating that “in the Gulf, governments purchase books for public libraries. Here, we’re left alone.”

He added that book fairs, once seen as opportunities for exposure, now offer little support. “Without institutional buyers, sales depend entirely on individuals, which is unsustainable.”

Memories Replaced by Merchandise

The street still bears the name Al-Mutanabbi, but longtime visitors say its spirit has changed. Veteran reader Ali Kareem remembers a time when it brimmed with rare editions and heated discussions. “Three decades ago, this street was full of rare books and valuable sources,” he told Shafaq News.

“Now it feels like a regular market.”

Elegant shops have vanished from the main road. The presence of Iraq’s leading authors—once a common sight—is increasingly rare. Tourists and new visitors often find themselves surrounded by toys, souvenir stands, and general retail.

“It’s difficult to even find a proper bookstore now,” Kareem added.

Holding On—One Shelf at a Time

Some of Iraq’s most historic literary institutions still operate here, but many say they can no longer rely on books alone.

Jassem Risan, who manages one of the remaining literary outlets, admitted, “We had to adapt. Now we sell printers, backpacks—whatever helps us pay rent.”

Meanwhile, retailers dealing in supplies argue they’re simply meeting evolving needs. “Demand peaks during the school season,” one vendor explained. “Families, ministries, and offices all come here. Business is steady.”

What remains clear is that Al-Mutanabbi Street stands at a crossroads. Without a shared vision to protect its cultural role, its remaining literary soul risks being buried beneath the tide of short-term commerce.